One of the founders of Abstract Expressionism is finally getting the recognition she deserves

By William Corwin

Imagine the atmosphere of a crowded and murmurous second-floor loft on Eighth Street in Greenwich Village in 1949: smoky and smelling not a little bit of unwashed clothes, Ballantine Ale, and whiskey. It was a raucous, chaotic atmosphere, full of macho posturing and empty threats (since this is art after all). In the early days of The Club, the storied Abstract Expressionist hangout in the East Village, there were only a handful of women in the room: among them the aristocratic Mercedes Matter, the streetwise Elaine de Kooning, and an intense dark-haired painter, Perle Fine. Working class, as were many of the other Abstract Expressionists, Fine put herself through art school and taught to pay the bills. Then, in those first five years following the end of WWII, at the invitation of a peer, the dashing Willem de Kooning, she found herself a founding member of a group of artists that at that specific moment in art history was determining the direction of Western art in the 20th century.

Cool Series No.7, Square Shooter, ca. 1961-1962, oil on canvas, 40 x 40 in.

© A.E. Artworks. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

In terms of painting, Fine was many things; historically, she helped define Abstract Expressionism. Her practice flirted with Neo-plasticism, and as a protégée of Mondrian she was enlisted to help keep the Dutch artist’s legacy alive after his sudden death in 1944. Fine also pursued a multi-media approach to painting; mid-career she embraced hard-edged pure abstraction—in direct dialog with Rothko, among others—and then in later life she experimented with Minimalism.

Like many of the American artists who came to prominence in the postwar period, Perle Fine came from humble beginnings and was energized by a new social acceptance that regular people could become artists, particularly in New York, while bolstered by some of the post-Depression artist-focused programs of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), though she did not directly benefit from the WPA employment opportunities. These programs were transformative in that they pushed the notion that an art career could be pursued by anyone and was no longer an aristocratic pursuit or family business.

Born in Boston in 1905, the daughter of immigrants from Russia—Sarah and Sholom Hyamovitch—who started a dairy farm in Malden, Massachusetts, Poule Feine (as her name is recorded on her birth certificate) became known as Perle Fine. She trained in illustration and graphic design, first at the School of Practical Art in Boston, but then moved to New York in the late 1920s and continued at the Grand Central School of Art, where she met her husband, Maurice Berezov.

She committed to “fine art” painting and studied at The Art Students League in the early 1930s. Immersing herself in the numerous galleries in New York and visiting the recently opened Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) to catch up on all the current trends in European painting, she devoted herself to abstraction early on. Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine, a detailed and thoughtful biography of the artist by Kathleen L. Housley, presents an engaging narrative of a New York School artist, resonating with the lives of Nevelson, Rothko, and many others of similar backgrounds.

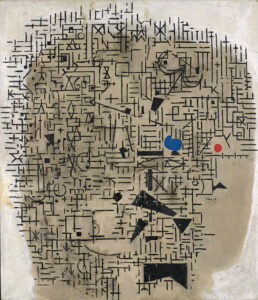

Bristling, 1946, oil and sand on canvas, 44 x 38 in.

© A.E. Artworks. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

The radical works that defined Fine’s career were produced in the 1950s and early ‘60s. Fine and her husband, also an artist, had jumped at the chance to study with Hans Hofmann upon the opening of his painting school in 1933. Hofmann and Fine had a productive teacher-student relationship; however, Fine was decisive and obsessed. Like her teacher at The Art Students League, Kimon Nicolaïdes, Hofmann after a point felt there was no more he could impart to the intense and driven young woman. While studying with Hofmann in the ‘30s, she embarked on a course of action to create abstract form that transformed painting from a picture of something into the actual thing itself. Fine’s works rejected figuration so completely that she was afraid to show them to Hofmann (and maybe she was also afraid he would steal her ideas). Always determinedly individualistic, Fine needed to retrace the steps of modern painting herself, moving from Cézanne to Cubism, on to Neo-plasticism and Mondrian, and finally, in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, arriving at a dual approach to painting embodying a soft and diaphanous touch versus tortured and cacophonous emotion.

In Untitled (Prescience) from 1951, a throbbing all-over background of rose, salmon, and peach is overlaid with scattered, soft-edged, but solid-colored green and blue forms. While these glyph-like objects are distinct from the surrounding pink, they rest gently on the surface. Painting #67, also from 1951, is very similare in format. Contrast these to works from Fine’s alternative trajectory: Tournament and The Wave, Roaring, Breaking (Gardenpartie), both from 1959. While the two canvasses are from the late ‘50s, Fine had been painting in this style since at least the very beginning of the decade. In both, the notion of a background is scrapped. Instead, competing forces clash across the volume of the canvas. Shards of color and amorphous blotches, sometimes multi-layered and deceptively volumetric, vie for prominence. In The Wave, script-like jagged lines stagger amongst the patches of color and expand outwards, creating a nexus of activity emanating from the center, whereas in Tournament, lines are less prominent, instead acting as frenetic lightning bolts momentarily emerging and receding.

Tournament, 1959, oil and collage on canvas, 57 1⁄4 x 135 3⁄8 in.

© A.E. Artworks. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

Fine’s credentials were expanded when she joined the American Abstract Artists (AAA) in the early 1940s. The AAA endeavored to introduce to local artists the refugee European artists streaming into New York during the German occupation; it was, in fact, through these introductions that Fine established contact with Piet Mondrian.

As a devotee of Mondrian from the first appearance of his works in New York museums and galleries, Fine was now able to watch the Dutch master in action in his New York studio. She was fascinated by his rigorous methodology, and as well as the spiritual power that he attached to his use of color and its precise application. We see her deep appreciation of Mondrian in her work in Bristling (1946). A confounding labyrinth floats over a bulbous beige form on a mottled white background. The precise black lines are occasionally intersected by simple forms: X’s and diamonds, irregular black polygons, and a red dot. Like a Mondrian, it has a definite, even if perhaps difficult to comprehend fully, order and playfulness. It presages both Fine’s more tempestuous assemblages of painted objects of a decade later, and her neater hard-edge Cool and Accordment series.

Arriving, 1952, oil on canvas, 50 x 49 1⁄2 in.

© A.E. Artworks. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

Fine found the drunken, garrulous atmosphere of the Cedar Bar (or Cedar Tavern) distasteful, as did many women on the scene. She was content to work in her studio on Tenth Street and was a founding member of the Tanager Gallery, an early artists’ collective, where she exhibited after a stint at the Willard Gallery, the Karl Nierendorf Gallery, and after Betty Parsons cut her loose after three shows with few sales. Fine was included in the legendary Ninth Street Show in 1951, one of the nine women along with Mercedes Matter, Lee Krasner, Grace Hartigan, Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Elaine de Kooning, Anne Ryan, and Sonia Sekula.

Despite her talent and associations, Fine did not find the financial success or notoriety that many of the other Abstract Expressionists experienced. Fine opted for a stable teaching career at Hofstra College and relocated to Springs, New York, on Long Island, pursuing a careful experimental methodology in painting very influenced by Mondrian’s practice. She would try different materials such as silver foil in her painting, as well as textured or even three-dimensional appliqués to the surface of her canvasses. Fine was never one to bend to the demands of the market. This also accounts for her widely varying styles—she was pursuing the interests of her practice.

While Fine’s experiments with texture, material, and geometry seemed esoteric, they were ahead of their time, influencing a new generation of painters from Frank Stella and Larry Poons, Robert Rauschenberg to Ronnie Landfield. Fine’s process was one of trying and exhausting every possible pathway she could conceive in her painting. This came in part from Hofmann, who encouraged students to constantly re-frame their perspective—ripping up works, re-arranging, and re-composing them. While her process had happily led to an intersection with the painterly freedom of Abstract Expressionism, she was not an action painter and definitely not the kind of painter to cling to a popular style, as she was an artist who felt a powerful need to experiment with other possibilities. She shed unnecessary gesture and form, alighting on a hard-edge abstraction seen in her Cool series.

The Wave, Roaring, Breaking (Gardenpartie), 1959, oil and collage on canvas, 68 x 94 in.

© A.E. Artworks. Courtesy Berry Campbell, New York.

A series of paintings in two colors, Cool paintings show Fine dissecting the figure/ground relationship and questioning perception, a line of discovery that informed her later work. In Cool Series No. 7, (Square Shooter), ca. 1961–1962, formalistically, Fine owes a debt to Rothko (with whom she was close), but an even greater one to Mondrian. Unlike Rothko, who trafficked in emotionally triggering assemblages of color, Fine is instead employing an optical game—first dividing the canvas in deep blue and bright red, and then inscribing a red square on the lower blue half. The implication is volume, even though there is nothing more than the simplest geometries. Her later optical works, which included three-dimensional appliqués, would also pursue this idea of implied space.

Simpler and simpler, in her final series, Accordment, Fine was focusing on the all-over-ness of the canvas, creating fields of color and enigmatic mathematical gesture. Her Accordment series, beginning in the late ‘60s and carrying through to the end of the ‘70s, was the last series of paintings she created before succumbing to dementia. Her late practice intersected with the subtle mark-making grids of Agnes Martin. While Fine is channeling Mondrian again, she is not highlighting the grid or geometricity so much as creating a gentle and regular net or pattern of marks as a means of presenting color and further suppressing imagistic proclivities. In A Crossing Thought (1970), a serene chocolate background is divided into narrow channels by alternating pairs of precise red and white vertical line segments. Blue curved segments appear to wriggle across the brown expanse, behind these oppressive lines. Like a Mondrian, the colors flicker, while the space of the painting is simultaneously inscrutable and mesmerizing.

Perle Fine, to a degree, was punished for her independence from a recognizable style-based market, as much as she was for being a woman. Fine could not join the Irascibles in their letter against the “American Painting Today” exhibition in 1950 at MoMA because she was actually included in the exhibition. This deflates the myth that Abstract Expressionism was purposely excluded from the show—it was merely Abstract Expressionism painted by men that was excluded.

Always a known quantity, Fine was represented in several exhibitions at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery, was well-reviewed by critics like Clement Greenberg, and saw her work added to important museum collections. But it wasn’t until she was featured in “Women of Abstract Expressionism,” curated by Gwen Chanzit at the Denver Art Museum in 2016, and then in “Inventing Downtown: Artists-Run Galleries in New York City, 1952–1965,” curated by Melissa Rachleff in 2017 at the Grey Art Gallery, New York University, that her rightful place as a founder of Abstract Expressionism and an influential voice in mid-century American painting was confirmed.