Anastasia Samoylova is an American artist originally from Russia whose work spans observational photography, highly-constructed sculptural images and installations. Across these forms she uses color, light, and carefully-layered compositions to investigate themes like urban development, the power of images in society, and our everyday experience of living with the climate crisis.

Her ongoing project FloodZone, nominated for the 2022 Deutsch Börse Photography Foundation Prize and published as a book by Steidl, visualizes global warming very differently to how we’re used to seeing it. Clichéd images of icebergs melting, decimated buildings or people struggling in the aftermath of storms, severe droughts and heatwaves suggest singular, colossal events rather than the process we are all living through. Instead Samoylova shows us the steady creep of decay that is the quotidian background to life in a city in the richest country in the world. Miami sells itself as an American paradise of pleasure and abundance, but in reality inequity is rife and the city is built on literally shifting sands; the swampland that makes it particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events and flooding.

In this interview for LensCulture, Clare Samuel speaks to Samoylova about FloodZone, how she pays homage to her photographic influences in several projects, and the relationship between photography and place.

Clare Samuel: How did you start making FloodZone, and when did you realize you wanted to take this visual approach to climate change?

Anastasia Samoylova: The roots of the project were speculative. They came from sheer observation of the place by simply walking the streets as a newcomer when I had just moved to Miami and began recording my experience. It was really my first foray into observational photography. I had seen Berenice Abbott’s Route 1 exhibition in Miami Beach, in which she photographed on the road from Maine down to Miami in the mid-1950s. It got me thinking about the relative scarcity of women in the genres of road trip, street and landscape photography. Perhaps an intersection of all three is what I ended up doing. So, environmentalism wasn’t at the heart of it at the beginning, even though this is what I studied—I originally wanted to be an environmental architect or designer, and all my projects have ended up addressing the environment in one way or another.

CS: Can you talk a bit about some of those initial observations of your new home?

AS: I moved to Miami in 2016 and it was the hottest summer on record. We experienced our first hurricane—a minor one but there was still flooding, which of course the bigger problem of rising sea-levels contribute to. The next year, in 2017, is when I realized how urgent the issue really is. We got hit by a Category 4 hurricane, which is not quite “the big one,” an expression Floridians use, but it was major and there was a mandatory evacuation order. I live in Miami Beach with my family, and we couldn’t evacuate because there was no gas left in the gas stations in the vicinity, which meant we could have run out of gas before arriving in a safe area. And there were no flights available anymore. There were some open shelters, but the evacuation wasn’t well organized. The information channels aren’t nearly as linked as you would expect in a place that’s been historically very vulnerable to such events. So, calculating all the odds, we decided to stick it out. We were one of the very few families who stayed in our condo.

We were lucky; the worst consequence for us was that the condo garage got flooded. There’s an image in the book of my son looking at it, wearing his bike helmet. We were en route to explore the damage in the neighborhood, which was quite substantial. Then of course the reports started flooding in about just how bad some other areas got hit. Thinking about the city’s lack of preparation led me to dig into some archives at the HistoryMiami museum where my current show is taking place—and it’s almost like the same story repeats over and over every few years.

The hurricane didn’t affect only South Florida. Many areas got hit worse, and I started thinking about the interconnectedness of events throughout this recurring catastrophe. The consequences are getting worse, yet it won’t affect everybody in the same way. People who own a third or fourth home in a high-rise building in Miami, won’t suffer in the same way as a multi-family home in the deep flood zone. So, it got me reflecting about what’s at stake, how this subsidized flood insurance isn’t going to necessarily pay for damage and the fact that not everybody can simply move away.

CS: What are some of the things you discovered in your research on the city and how did they feed into the way that you photographed?

AS: I wish I could find this early postcard, I think it’s from the 1920s, that said something along the lines of: “Florida, a perfectly lovely safe place with occasional summer storms.” By “summer storms” they meant hurricanes! Florida owes its existence, as this tourist haven and real estate opportunity, entirely to images. And as somebody who is committed to the study of images, I was drawn to how postcards and real estate brochures essentially made the place what it is. Color palette was one element. South Florida sits on an enormous swamp, and as you can imagine those browns and greens weren’t appealing enough to ‘sell’ it, so all these vivid hues were intentionally brought in to offset that. Pastel-colored buildings and the enormous pink sidewalk that runs throughout the entire island of Miami Beach, and so on.

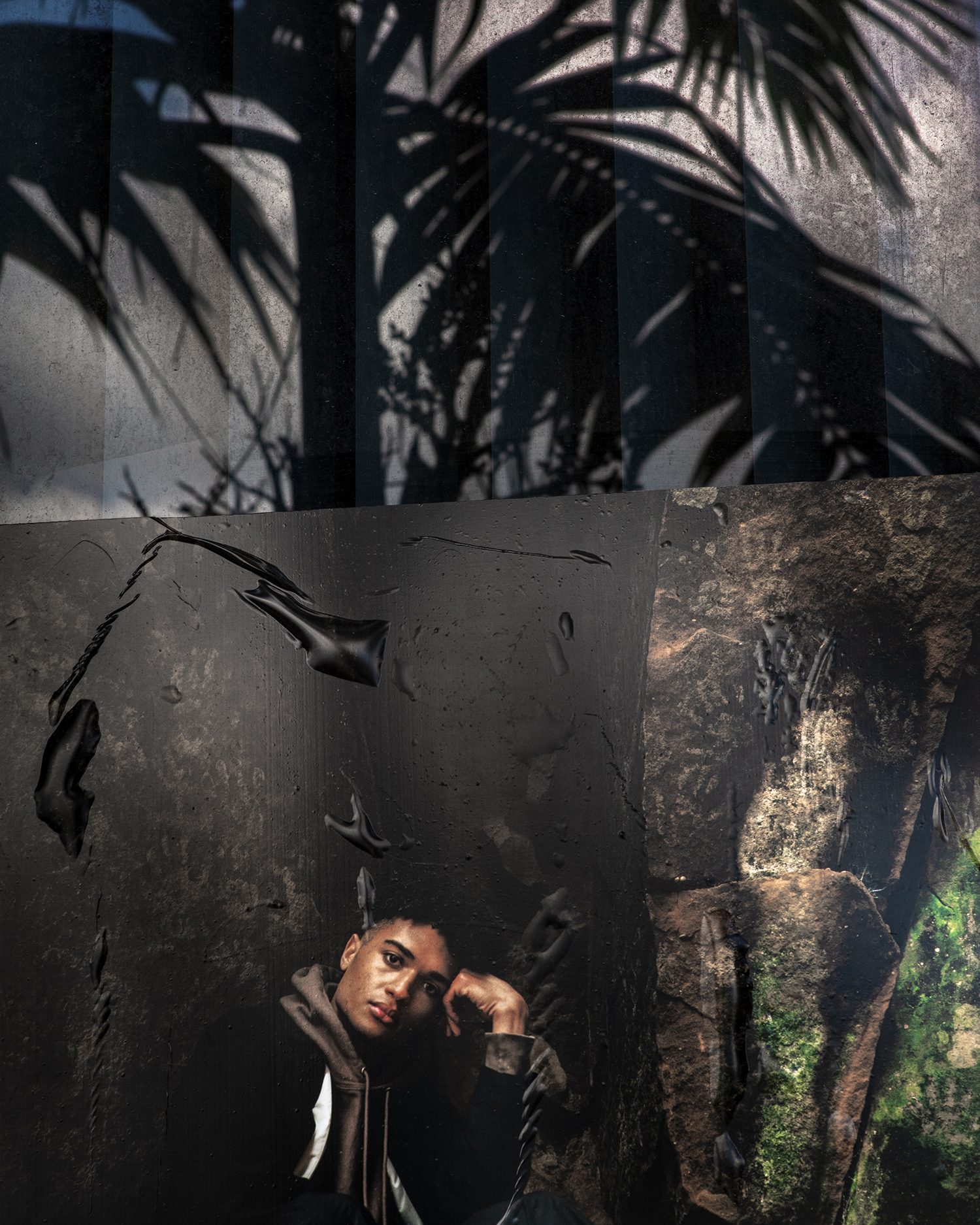

CS: You’ve said previously that “Miami is a life-scale collage,” and a sense of collaging that oscillates between two and three dimensions is something I see in all your projects. Collage makes me think of Dada and Constructivism, what is it about the form that fascinates you?

AS: Well since you mention Dada and Constructivism, I think in times when the world is in turmoil, collage seems to be artists’ choice of medium. It speaks to illusion, disruption—a kaleidoscopic reality where you can question accepted motifs. Both Dada and Constructivism emerged in ‘unprecedented times,’ like we have now where sometimes it does feel like the world is ending. The gesture of cutting—in photography it’s the art of cropping out and layering—is something I aim to achieve in my images. I deliberately avoid any obvious dramatic moments, motion rarely plays any role at all, so the ‘action’ is in the unpacking of many layers to look deeply beneath the surface

CS: You’ve said that FloodZone is an ongoing project. Where is it headed next?

AS: I like to circle back to my projects. They overlap and inform each other. So, it’s not as if I’m always shooting for FloodZone, but I’m more awaiting its next cycle. Then there’s this FireZone project that I began in 2019, which is obviously intertwined. Projects are dependent on practicalities too—funding, grants and opportunities. I’m thrilled that FloodZone is being exhibited widely right now. I didn’t know it was going to take off the way it has.

Currently, FloodZone is on view at George Eastman House until the end of the year exhibited as 60 images. The kind of response it’s generated is amazing, as well as the number of languages it’s been covered in around the world. I think partly the success has to do with how the global issue of climate change is looked at through its impact on a very particular place. Every place is specific. FloodZone really embraces that specificity, and through that people can see something more universal, I think.

CS: As you said, it sometimes feels like the world is ending nowadays. Do you experience climate grief or climate anxiety? Are some of the images more personal for you than others?

AS: The project certainly is more about ‘climate anxiety’ than any kind of direct reportage from disaster sites. We are all familiar with those kinds of images by now, and I think those sensational visual reports do nothing but make us want to give up. How many images of human suffering can you take? Something just happens to your heart, I think.

Regarding climate anxiety—despite the knowledge that things are indeed bad, and not nearly enough progress is being made, I remain an optimist. One of my favorite writers, Rebecca Solnit, talks about the importance of continuing to preach to the choir. Sometimes it feels like we’re in this bubble, we’re aware and we’re trying, but then, there’s this bigger world where you must still convince people that this is real and urgent, and they are not always responding. But I often do see a difference that my open-ended images make because they’re not depictions of catastrophes. When I exhibit them, they tend to generate dialogue across the board with people who might have not been initially receptive to the subject. They have led to conversations with people like developers and city planners. Reflection and communication are critical, and small solutions on a local level can contribute to something larger.

CS: Your latest book Floridas continues to deal with some of the subject matter of FloodZone, but in a different form. It’s a direct dialogue between your images and those of Walker Evans, who also photographed the state extensively. How did you come to this concept?

AS: I know it’s crazily ambitious to put my images in conversation with his! Although, you know, there’s also humor to it, and of course, it’s an homage. It was the idea of the book’s editor, David Campany, who had edited FloodZone. He knows my work well and is an expert on Evans. He understood how Evans’ project and mine are very much about this place, Florida, but also about how this state, with all its geographic, cultural, political and economic tensions, is really a microcosm of the USA as a whole, in extremis. Florida is a swing state and it’s never off the news, which makes it representative of all kinds of divisions. I wanted to focus on Florida because I’m an insider but also because of all the stereotypes and stigma around it. For all that, it’s a complex place that I think holds the key to understanding this nation.

CS: Can you tell us more about the different images that make up Floridas and the relationship between your two visions of the state?

AS: While environmental issues are still very much present in the book, the bulk of the project was shot in 2020-21, a very stressful time in the USA with the elections. It’s full of visual manifestations of people’s political views, atop the incredible natural beauty of Florida’s landscapes—some appearing almost untouched by civilization, and other places highly manipulated, like all the tourist attractions.

Evans made his photos of Florida between the 1930s and the 1970s. He was often accused of nostalgia, lingering on things from the past. And my Florida work has a solid dose of that too—looking at traces of the past in the present. Like Evans, I think we do need to understand where things have come from in order to understand how they are today. The present is always layered with the past, and you can see that layering in the work of both Evans and I, in different ways. We point the camera carefully at the world, frame it, and try to let its silence speak somehow.

Somebody once asked me: “So who’s the author?” I don’t think of myself as an author; again, it’s a collaboration. I’m happiest when I’m in a team, working with an editor, a publisher or a curator. The photography itself is made very much in isolation. I’m alone when I’m shooting and it is very intensive. Pure concentration. But all the stages that must come after this are collaborative. The selection, the sequencing, the making of books and the curating for shows. So I don’t think of my career or practice as a solitary thing.

CS: Who are your other photographic influences, and how did the project Breakfasts come about, where you actually include them within your images?

AS: I taught for a while and the history of photography was my favorite subject to teach. Breakfasts came out of my nostalgia for the history of photography class. Once I wasn’t teaching in the mornings anymore, I could finally have a proper breakfast rather than rush with my thermos to an early class. Eventually I combined the two—the new luxury of having longer breakfasts and my love for photography history in the form of photobooks that I began collecting as soon as I got my green card.

I would flip through my newly acquired photobooks, eat breakfast and get inspired. It’s a very playful project; it doesn’t come from the kind of cynical Pictures Generation impulse to appropriate. They are more homages. You can’t be a good writer if you aren’t a good reader, and I believe the same applies to visual literacy. You just cannot be a good photographer if you don’t know the history of the medium.

CS: What else are you focused on in your practice moving forward? As we speak, you’re in New York shooting for a project called Image Cities?

AS: The Floridas book was just launched in Madrid, and I’m designing exhibition concepts for that work. Image Cities is the project I’m very actively developing right now, shooting almost daily. This one is more emphatically global in its reach. I’m in New York now, but I’ve visited many European cities. I began the project in Moscow last year and will be in Tokyo soon.

Image Cities looks at the presence of images within the urban landscape, and at what those images demonstrate about culture, values and aspirations. I’m mainly photographing billboards and real estate renderings of future urban developments, in cities that are also holding on to their often grand imperial pasts. And this is where disparate places like Moscow, New York City or Paris have parallels. You’d be surprised how frequently one kind of propaganda is replaced by another.

CS: I know you’ve posted on Instagram about the war in Ukraine. Does what you shot in Moscow for Image Cities relate to that current reality?

AS: Yes, when I started shooting there in May 2021, it came out of this observation that Moscow is becoming like a brochure of itself, trying so hard with its presentation. I was questioning what it conceals. There are enormous printed facades on the buildings, and life-size ads promising this very utopian—and in terms of gender—very traditional society, which I found quite creepy. So it felt propagandistic, but not in the old-school way I was familiar with from growing up in the USSR period in Moscow. It reminds me of the placement of all those socialist realism posters, but with a new capitalist set of values embodied in life size images of the current order.

Obviously, there was no predicting what was to come. We suspected, but nobody expected this degree of insanity and barbarism. Now we know just how unfree it has been there all along. The gradual destruction of independent press and media, the mass exodus of intelligentsia, of freethinkers. The violent destruction of any possible opposition, and yet you’re being presented with this idealized image. A non-stop fictitious narrative that serves the state.

CS: Circling back to a comment you made at the start of our conversation about women in the genre of road, street and landscape photography, so much of your own work is about moving through cities and observing. Do you think there is a gendered element to that?

AS: The exhibition of Berenice Abbott’s work I mentioned earlier really made me think deeply about what it means for a woman to be in a public space. To me, the ability to wander was always important. I remember once I was 16, walking in Moscow, when I got stopped by some male security guard and made to delete my photographs from my digital camera. And that’s when I realized that I can’t just go around photographing freely. It feels like a feminist act simply to do that. There are some important images in the Floridas project of women alone and content in public space. Even if they’re just sitting on the grass or eating in a restaurant solo. It’s a symbolic gesture to be there, alone as a woman photographer, photographing these kinds of scenes. They may seem small, but they’re significant.

I recently read the Feminist City by Leslie Kern. She writes of how cities weren’t designed for women, yet the global population is increasingly urban. I think by 2050 over 60% of the world’s inhabitants will be in cities. The biggest demographic flowing into metropolises is women, because cities provide the most opportunities for independence and non-traditional roles. You can see it in advertisements everywhere—these beautiful faces and bodies, telling you that you don’t measure up. It’s across all our screens this kind of propaganda, but it becomes monumental as life size ads in the streets.

These images tell you so much about the values of a place, and they are aimed predominantly at women. It seems more opportunities come at the cost of higher consumption in the service of looking perfect. Who does that serve? What does it mean that the world looks at cities for environmental solutions, when cities are the biggest consumers of energy? These are serious concerns but I’m not a polemicist. None of these issues are addressed head-on in my work. All my projects present questions, and none of them hold the answers. It’s all about the propositions that I make to the viewer; the questions I’m most interested in right now.