Nine weeks that upended French Art

By Lilly Wei

It was July 1905 in Collioure, a quaint French fishing village sandwiched between the sparkling waters of the Mediterranean and the slopes of the Pyrenees located about half a marathon’s run from Catalonia and the Spanish border. Henri Matisse invited André Derain to meet him (and his family) there. The attraction? An azure sky and a dazzling light that gilded all that it touched: medieval buildings, lush foliage, red rock coves, all. As Derain vividly put it, in a letter to a friend: “The nights are radiant, the days are potent, ferocious, and victorious, the light bears down on all sides with its immense shout of victory.” The two became inseparable for the next nine weeks, churning out—in prodigious quantities—paintings and drawings of the same sun-blasted subjects: boats (so many that it seems they had painted the entire fleet between them), olive trees, the mountains, the sea, portraits of Matisse’s wife Amélie, each other, others. Derain’s portrait of a pensive, bespectacled Matisse is one of the finest that exists of him, a brilliant intertwining of Fauvist aesthetics and penetrating character study.

André Derain, Woman with a Shawl, Madame Matisse in a Kimono, 1905, oil on canvas.

Private collection, courtesy of Nevill Keating Pictures, London. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

This was before either of them was assured of more than a footnote in art history, if that. Although they had shown and were well-known among their contemporaries, who knows what might have happened had they not decided to go to Collioure together? But they did, and because of that the course of French painting shifted, inspired by each other as well as Collioure. Like explorers to uncharted territories, what their eyes saw was a previously undiscovered world of fresh, riotous color.

Given its significance for Modernism and its legendary pairing (recalling that of, say, Van Gogh and Gauguin), it is curious that the work from that seminal period has never been shown together in depth. “Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism,” curated by Dita Amory from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Ann Dumas from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is a welcome corrective. The show, a joint endeavor between The Met and the MFAH, debuted in New York this past fall and is on view in Houston from February 25 to May 27, 2024.

The exhibition is luminous, consisting of 65 paintings and works on paper; most are from those extraordinary weeks in Collioure, the paintings almost evenly distributed between the two artists. The works on paper, however, are almost all by Matisse, the watercolors particularly stunning. It was fascinating to compare the similarities and differences in their brushwork, their choice of colors, how they dealt with light, the points of view they preferred, and so on. Traces of perspective in the many diagonals that Derain used to structure his compositions (as in The Faubourg of Collioure) had all but vanished in Matisse’s work, while Derain went further than Matisse in renouncing pointillism’s mosaic-like system of tiny complementary dots and dashes. But, as the summer advanced, the older artist’s strokes also loosened up, influenced, no doubt, by the proximity of Derain (and the reverse) who claimed to have little use for pointillism. He said, “I’m completely over it and almost never use it anymore…it is detrimental to things that derive their expression from deliberate disharmonies.” Yet that’s not quite true. Some of Derain’s –and Matisse’s—best works here retain divisionism’s dabs of color, although the paint is applied more freely, its effect more emotive.

André Derain, Henri Matisse, 1905, oil on canvas.

Tate, purchased 1958. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Derain, who was impulsive, enthusiastic (but could also be moody, discontented), worked rapidly, with fierce concentration, completing 30 paintings and a cache of drawings and sketches in that time. Afterward, he never returned to Collioure; it had given him—or he had taken—everything from it he needed. In remarks he made to author and art historian Georges Duthuit in 1929, he recalled: “Colors became sticks of dynamite. They were primed to discharge light. It was lovely, this idea, in its freshness, which could be taken well beyond reality.”

Matisse progressed more deliberately. His production was mostly made for reference, and many of his creations were rough, unfinished. He went back to Paris with 15 paintings, 40 watercolors, and around 100 drawings, to be reworked. He, unlike Derain, returned to Collioure repeatedly for nearly a decade, often for long stretches of time. It was a place to recharge, singularly important to him as the place that first revealed to him, in a “pure way,” what he wanted to express in his paintings. It revealed color to him, and the extent of its “force.”

Upon their return to Paris at the end of the summer, both Matisse and Derain submitted works based on their summer in Collioure to the Salon d’Automne. Established a mere two years earlier, in 1903, it had already become prestigious as an annual showcase for contemporary art, admittance highly competitive. They were both selected (as were Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen, Albert Marquet, Charles Camoin, and Jean Puy), to the subsequent outrage and scorn of critics and the public—and the vociferous acclaim from radical, like-minded artists. Christened les Fauves (“the wild beasts”) by Louis Vauxcelles, a journalist, who, it seems, meant the term to be more descriptive than pejorative, referring to the group’s unorthodox, subjective use of dissonant colors that were unshackled from reality. Veering away from truth to representation in favor of truth to painting, the Fauves illustrated Maurice Denis’s pronouncement that a painting, before it was “a war horse, a nude, or an anecdote of some sort—is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.” Matisse, the oldest of the group, was deemed its leader (an artistic movement that was short-lived and never formalized) and Derain his most talented disciple, who bore the brunt of the ridicule. But brief as its existence was, its impact was profound, Matisse remarking, “Fauve painting is not everything, but it is the foundation of everything.”

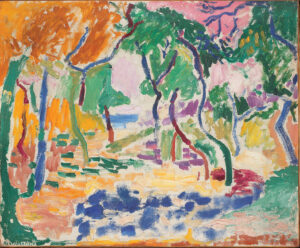

Henri Matisse, Landscape at Collioure (Study for “The Joy of Life”), 1905, oil on canvas.

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In addition to catapulting painting into exciting new terrain, the rewards for Matisse and Derain from their Collioure adventure were immense on a more mundane level, proving that, (almost) always, even bad press is better than no press. Because of the notoriety of the paintings, Matisse met the Steins—Gertrude Gertrude, Leo, Sarah, and Michael. They bought Woman with a Hat, 1905, his now iconic portrait of Mme Matisse, immediately recognizing its importance despite the uniformly harsh judgment of the critics. The Steins introduced him to sisters Claribel and Etta Cone, all of whom would become ardent American supporters and crucial to his career. Derain, also thanks to the scandal of such unorthodox approaches to painting, was taken up by the canny Ambroise Vollard, who would become one of the preeminent dealers of French contemporary art of the period (representing, among others, Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Picasso). Vollard bought all the work in Derain’s studio from the summer and commissioned him to paint a series of views of London, establishing his career.

Derain’s reputation is now primarily based on his three years as a Fauve, although he had a long and successful career. His pictures in this exhibition are knockouts, reinforcing that evaluation, and, because lesser known, his work is the more revelatory. His sense of urgency is contagious, the heat of his palette twirled to high, matching the weather: pure reds, yellows, oranges, and whites. He would often use paint straight from the tube, the effect raw, percussive, startling, new. He drank in Collioure avidly, in great visual gulps, writing to his friend Vlaminck about its “explosion of colors,” how ravishing and overwhelming it was, and how unaccustomed he was to so much sunlight.

For the full story please subscribe below: