The “Death and the Maid” show invites reflection through timeless memento mori, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

By Lilly Wei

When London-born artist Cecily Brown landed in New York City, where she has lived ever since, it was 1994, about a year after graduating from the Slade School of Art. She came to the United States as a budding painter in rebellion against the conceptual inclinations of the Young British Artists (YBAs). Brown, you might say, became a standard-bearer for another kind of YBA. After all, she was also young, British, and an artist—one, however, who exuberantly and fearlessly wielded a brush dipped into thick dabs of (wonderfully) messy, smelly, voluptuous paint. She arrived at a time when the medium, declared dead in the 1970s, was undergoing a resurrection, a rehabilitation. Her paintings, assuming a non-partisan stance, embraced both abstraction and figuration, toggling between the two: some more figurative, others more abstract. They were, and are, densely painted, the eye stumbling over the brushwork, the imagery tantalizingly elusive as if playing hide-and-seek with the viewer, surfacing, submerging, in visual turmoil, collision bound. Her color scheme often suggests rococo boudoirs: pinks, roses, corals, mauves, creamy whites, yellows, pale greens, and blues. It can also burst into a more operatic strain, dominated by the most vivid of reds, the sensuality and earthiness of content and medium well matched.

No You for Me, 2013, oil on linen, 83 x 67 in.

Private collection, courtesy Tracy Williams Art Advisory, New York © Cecily Brown.

Brown left London because she believed that New York would be more receptive to her approach to painting. She said that while it might be hard for a white male artist to work in an Abstract Expressionist mode at the time, she, as an English woman in her 20s, might get away with it. (She was right.) And she was not merely enamored with Willem de Kooning, Philip Guston, Joan Mitchell, and other Abstract Expressionists, but also the art of the past and the

present—from Frans Snyders, Pieter Brueghel, and Bosch to Fragonard, Boucher, Chardin, and Manet, to Chaïm Soutine, Francis Bacon, Georg Baselitz, and so on, practicing her own version of appropriation, of challenge and homage. It was inevitable that she would attract attention. And she did, almost immediately. Her formal prowess, always prodigious, as well as her confidence, was enough to make one suspect that a Faustian bargain had been struck. (Indeed, she has claimed that the devil “has all the best tunes.”)

Now, after almost three decades of acclaim, Brown is having her first museum survey in New York at one of its and the world’s preeminent venues: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Organized by Ian Alteveer, Aaron I. Fleischman Curator of the museum’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, it is accompanied by a beautifully illustrated catalogue with an essay by Alteveer and a conversation between the artist and Adam Eaker, Associate Curator in European Paintings; both texts are wide-ranging and informative. Brown, unlike some artists who are indifferent to titles, weaves them into the narrative of the work and keeps notebooks of possibilities on reserve for future use. The provocative name of this show, Death and the Maid, the title shared with the most recent painting in it, is borrowed from Franz Schubert’s poignant lied, which she purposefully changed from Death and the Maiden (Der Tod und das Mädchen) to Death and the Maid, a small but significant alteration, updating and inflecting its sexual and social connotations. The lyrics are from a poem by Matthias Claudius that describe Death offering himself as the ultimate lover to the young woman he has come to fetch, soothing her fears, seducing her into acceptance. (Brown is right again; the devil does have the best tunes, as well as the best lines.)

All ls Vanity (after Gilbert), 2006, monotype, 47 1⁄4 x 36 7⁄8 in.

Private collection, courtesy Two Palms, New York © Cecily Brown.

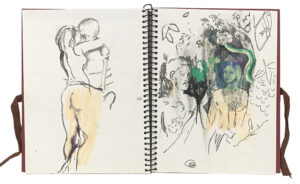

It is a tightly themed show, the approximately 50 paintings, works on paper, and sketchbooks (always fascinating to see, like looking over the shoulder of the artist at work) focus on the concept of vanitas. (One is reminded of Ecclesiastes: “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity.”) Reminding us of the brevity of our lives and the futility of worldly possessions and hedonistic pursuits, the exhibition pictures domestic interiors and bucolic pastimes, still lifes and extravagantly appointed tables. The twist, however, are the mirrors, skulls, skeletons, and other memento mori making star turns throughout, sometimes immediately evident, but more often revealed only upon looking closely. The recurrence and variation of motifs give structure and deeper resonance to the presentation—and while its foregrounding of the relentlessness of time, senescence, and death may strike some as morbid, who has not thought of mortality in far more immediate, intimate terms over these past three years? And why not acknowledge what is the most momentous event of our lives? After all, the end of life is something we will all experience since death, I’m told, is not optional.

Vanitas as a theme, as well as mirrors (mirroring and doubling), emerged in Brown’s work as early as 1997, the year of her painting The Only Game in Town, which features a woman gazing into the mirror of her dressing table. All Is Vanity (after Gilbert), a monotype from 2006, depicts another woman staring into the mirror at her reflection and is based on a popular 1892 drawing by the American illustrator C. Allan Gilbert. The woman sits at her vanity (note the pun), her face and her reflected visage merging to create the orbital openings of a skull, the arms and hands forming its mouth. However, that image glimmers from within yet another mirror placed parallel to the picture plane, looking outward from the pictorial space as if to register what’s in the space of the viewer, recalling Velázquez’s brilliant perceptual conundrums in Las Meninas.

Sketchbook, ca. 2004; oil pastel, ballpoint pen, and graphite on paper; overall (open) 7 3⁄8 x 12 in., (sheet) 7 3⁄8 x 5 5⁄8 in.

Private collection © Cecily Brown.

In Aujourd’hui Rose (2005), a large, slightly earlier cream-and-rose painting—Brown effortlessly shifts from extra-large to small formulations—the skull appears again, this time created by two girls facing each other, holding a small dog that nestles between them. Their heads become its eye sockets, the dog its nasal cavity, and the edge of their seat, perhaps, the stiffly upturned, mocking or menacing mouth. Taken from a Victorian postcard, the visual game it plays is like the famous duck/rabbit drawing in which you can’t see both images at once; it’s either the duck or the rabbit. Here, it’s either the skull or the girls (or the skull or the women described above). The picture is clear, reinforced by the title, a nod to Ronsard’s often quoted line of verse: “Cueillez dès aujourd’hui les roses de la vie.”

Fair of Face, Full of Woe (2008) also spins a merry nursery rhyme into similar terrain. A modestly sized triptych, its surface agitated, is linked to landscape and the pastoral by the abundance of yellows and greens, but within the vernal flourishing, the death’s-head is again present, like the serpent in the Garden of Eden. The Picnic (2006), another triptych, is an expansive 10-feet-wide jumble of paint and food-ladened platters arrayed on a bright white tablecloth, as Dutch and Flemish still life crash into intimations of Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, the surface convulsive, everything seeming to spill out, the points of view multiple: Are we looking down, at eye level, or up?

Interiors such as those in Hangover Square (2005) show us a pre-Marie Kondo world in which not everyone considered tidiness a virtue. A chamber of elegant proportions, shown in utter dishevelment as if after an orgy, reminds us of Brown’s interest in Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress, and perhaps her time spent cleaning the homes of friends early on to support herself, as suggested by Alteveer. (We can only wonder what those homes she cleaned might have looked like afterward, if her paintings are any indication.) Yet, despite the clutter, there is clarity in the composition and a comprehensible progression into the pictorial space that isn’t always present in her more tumultuous allover works. In the even more crammed Selfie (2020), the chaos is again restrained by a semblance of a grid in the background and the same steady entry into the painted space. It depicts the interior of a studio revealed in variations of a primary palette that is chock-a-block with paintings, although some of them may be windows, à la Matisse. And are those strokes of pink and rose a nude model in the forefront? A self-portrait? It summons up memories of Bacon’s notoriously disordered studio, surely a candidate for all-time messiest, an artist she knew and admired. It might serve as her interpretation of an atelier painting or a kind of retrospective. It also brings to mind another category of painting in which, installed from floor to ceiling and scattered about, the paintings were the subject, often used as advertisements for selling purposes in a time when reproductions were not easily accessible. Antoine Watteau’s exquisite Gersaint’s Sign (1720-21) is a masterpiece of this type, as well as simply being a masterpiece.

Maid in a Landscape, 2021, oil on linen, 17 x 23 in.

Private collection © Cecily Brown.

In an exhibition about vanitas, still life (or nature morte, the less euphemistic French term for it) occupies a central role. It became an independent category in Netherlandish painting around the mid-16th century, freed from its religious origins, although it retained its associations with mortality and transience. Brown’s small, succulent Nature Morte (2020), which features a lobster and lemons, is closely modeled on a painting by Willem Kalf (a sought-after still life artist from the Dutch Golden Age), her recumbent lobster lust-inspiring, thanks to its improbable, gorgeous reds, the eroticism in the paint itself. The much grander Lobsters, Oysters, Cherries and Pearls (2020), a feast among the ruins, is even more entangled in marks flash-flooding the surface, a study in decadence, wastage, greed and gluttony (two of the deadly sins), the guests abruptly dispersed, the golden-eyed black cat (the Devil’s familiar) lurking beneath the table, watching, waiting. And if you say the title aloud, the luscious slurp of the “er” sound in lobsters, oysters, cherries, and pearls is a perfect combination of sound, sense, and image.

There is much to engage the viewer in this exhilarating exhibition, so plunge into its trove of visual treasures, hidden and otherwise, allusive and illusive. While the themes might be dark, insisting on tempus fugit and the eschatological, the paintings are not. There is too much color, heat, and light for that. Brown’s cavorting, teasing, impassioned brushwork sends a far different message. And let’s not forget one more maxim: Ars longa, vita brevis.