An unusual exhibition foregrounds the Renaissance and Baroque art of painting on surfaces of semi-precious stone, marble, or slate.

By Rebecca Allan

Anyone who has hiked a mountain or combed a beach to seek out unusual stones can appreciate our shared affinity for the special qualities of rocks—their age, origin, resilience, coloration, textures, and shapes. Natural rocks such as limestone, marble, and slate, formed over millions of years by heat and pressure applied to organic matter, connect us to Earth’s geologic history. It is no surprise that quarried stones became a desirable resource for artists, as surfaces for their paintings, during a particularly innovative period in Europe between the 15th and 16th centuries.

Gerard van Spaendonck, Grapes with Insects on a Marble Top, circa 1791–95, oil on marble, 7 3⁄8 x 9 1⁄4 x 1⁄8 in.

The Frick Collection, New York, Gift of Asbjorn R. Lunde, 2012; © The Frick Collection

“Paintings on Stone: Science and the Sacred 1530–1800,” an exemplary exhibition at the Saint Louis Art Museum (through May 15), brings together more than 70 artworks by 58 artists, featuring 34 different kinds of stone. The initial inspiration for this cross-disciplinary project grew from a commitment made over 20 years ago by Christian B. Peper (1910–2011), a longtime patron of the museum and reader of classical literature, to support the purchase of a small oil painting on lapis lazuli panel by Giuseppe Cesari (1568–1640). Perseus Rescuing Andromeda is a smoldering, jewel-like painting, no larger than a hand mirror, that catalyzed 15 years of research culminating in this endeavor. Organized by Judith W. Mann, Curator of European Art to 1800 at the Saint Louis Art Museum, the exhibition includes rarely-seen works transported to Missouri from public and private lenders across the globe, assuring that it is a once-in-a lifetime occurrence.

A relatively unknown aspect of European Renaissance and Baroque artistic practice, painting on slate, porphyry, agate, lapis, and other valuable stones reflected interests in the relationships between art, geology, and philosophy. As nature’s most durable material, rocks were sought out as painting surfaces not only for their aesthetic beauty but also to reinforce a metaphorical and physical connection with eternity. The incorporation of stone as a surface for painting during the Italian Renaissance also catalyzed philosophical debates about mimesis—the relationship between art and nature—and the paragone—the question of the relative superiority of painting and sculpture. Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Giorgio Vasari were among the artists and writers who participated in this comparative argument.

Cavaliere D’Arpino (Giuseppe Cesari), Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, circa 1593–94, oil on lapis lazuli, 7 15⁄16 x 6 1⁄8 x 1⁄4 in.

Saint Louis Art Museum, Museum Purchase 1:2000

Scholarly research into Renaissance art evolved, over time, from a primary interest in the subjects of painting to an exploration of how techniques reinforce subject matter. Since most paintings from the 16th and 17th centuries were executed on wood, linen, or canvas (and occasionally copper), the later discovery that stone was actually more common as a painting surface has led to a richer understanding of this tradition. In the 1970s, researchers looked more closely at the sourcing, dissemination, and use of stone. Originating with Italian artists who sought out stones and developed techniques for their use, this practice expanded to workshops in Antwerp, Nuremberg, Prague, Seville, and other cultural centers in Europe.

Stones that have been quarried, cut, and polished have been utilized as surfaces for painting since antiquity. There are ancient Greek examples of mythological and domestic scenes painted on marble panels, as well as 7th-century icon paintings on treated marble (coated first with wax and gilding) at Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, depicting subjects such as the sacrifice of Isaac and Jephthah’s daughter. In the 13th century, paintings of apostles in the Basilica of St. Ursula in Cologne were rendered on slate.

In 16th-century Venice, a revival of interest in the classical world, furthered by archaeological discoveries and the printing of Greco-Roman texts, was coupled with an influx of Near Eastern materials. These cultural intersections prompted artists to experiment with new techniques as well as to create works on stone that they believed would last forever. In some classical Greek writings, rocks represent the origins of humankind, while in the Bible they are associated with sacred imagery.

Cavaliere D’Arpino (Giuseppe Cesari), Italian, Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, 1594–95, oil on panel, 20 11⁄16 x 14 15⁄16 in.

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, Image courtesy of the Clark Art Institute

The Venetian painter Sebastiano del Piombo (1485–1547) is credited as a pioneer of—if not the first to develop—the “secret” methods for oil painting on stone. Each type of stone has its own particular density, texture, coloration, thereby influencing a painter’s ability to impart coloration, and to exploit the reflective properties of stone for naturalistic effects. Chemical analysis of these techniques (including their reproduction in the laboratory by conservation scientists) has shown that the process involved the application of a mixture of melted wax, resin, and hot oil to the support to prepare the stone surface before painting. Given the slippery or varying surface textures of different stones, we can imagine the necessity of an intermediary layer to assure the bonding of oil-based pigments.

The most desirable stone in the classical era was marble, favored for its high polish, durability, and color absorption. By 1530, Renaissance artists had begun painting sacred images and portraits on marble, and then increasingly on slate, which was more easily sourced. Slate occurs in ranges of warm to cool gray tones; it has a chalky, relatively opaque surface and contains thin slivers of mica within its structure that produce a softly glowing quality. Working on slate, artists could easily achieve a broad coloristic range with fewer pigments. By the late 1700s, artists were using a wide array of luxurious stones including agate, alabaster, amethyst, jasper, lapis lazuli, and onyx. The sourcing of these rare stones reflects the extensive industries of mining and transport. These international networks are discussed in depth in a compelling essay by Mario Casaburo in the exhibition’s catalogue.

In her catalogue essay, curator Judith Mann writes that when the Saint Louis Art Museum acquired Cesari’s Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, no one could imagine that it would be the focal point for her exhibition. The painting’s eight-inch high lapis lazuli support, Mann emphasizes, was rather significant during a period when most lapis supports were “butterflied”—that is, made by slicing the material and lining it up along its cutting edge, forming a mirror image. One of at least 10 versions of this subject painted on seven different supports by Cesari, the St. Louis picture represents Perseus aloft on the horse Pegasus preparing to vanquish the sea monster Cetus and rescue Andromeda, who is chained to a rock. Using stone as a support for a subject bound to a rock must have provided intellectual delight for the artist as well as his patrons. The saturated ultramarine blue hue of this semiprecious stone, with its small flecks of calcite and crystals, added to the high status and worth of such an intimately sized object. Take note: ultramarine pigment was reserved almost exclusively for painting the Virgin Mary’s garments; thus it was one of the rarest and most expensive colors.

Francesco Salviati’s Portrait of Roberto di Filippo di Filippo Strozzi is painted in oil on red and black African “marble.” Not a true marble, it is actually a rock known as breccia, a type of limestone that has been fractured into angular pieces and then naturally re-cemented by calcite. The cherry reds, blacks and icy whites are the result of impurities in the limestone. Salviati complements the red with an emerald-green-painted background, and he leaves the outer edges of the circular stone support unpainted, a possible reference to the sitter’s biography. Strozzi lived in Florence until 1538, when he was exiled. It could be that the artist revealed the stone support because he understood Florentine taste for colored marbles. Furthermore, the circle within a crescent resembles the Strozzi family’s coat of arms.

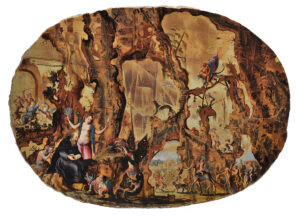

Jacob van Swanenburg, Temptation of St. Anthony, circa 1595–1605, oil on pietra paesina, 24 5⁄8 x 20 5⁄8 x 2 7⁄8 in.

Kunstkammer Georg Laue, Munich/London

Jacob van Swanenburg’s Temptation of St. Anthony is painted on pietra paesina. Also known as landscape stone, it is patterned with crisscrossing lines—the result of limestone having been infilled with thin calcite veins. This material originated on the ocean floor and also contains iron and manganese. In popular 15th- and 16th-century literary accounts, St. Anthony was described as a hermit whose piety was threatened by evil beings. Here, seated and reading in his black robes, he is tempted by a woman with a mirror and peacock feathers. A wake of vulture-like serpents and tormented half-human beings likely refer to the popular theme of vanitas, the fragile impermanence of life on earth. Jacob van Swanenburg specialized in extraordinary representations of hell. Combining the painted (illusionary) forms of irregular rocks against the actual, amber-colored stone surface with its geometric patterns, he heightens the tension between the eternal and the ephemeral. Working in Rome at the time he made this painting, he may have been introduced to pietra paesina by the Florentine artist Antonio Tempesta.

The mimetic relationship between the subject of an artwork and the material of its making is evident in Interior of the Jesuit Church in Antwerp, an oil on marble by Wilhelm Schubert van Ehrenberg. The artist cleverly left the white marble unpainted on the lower levels, columns, galleries, and chapel, unifying the stone support and his illusionistic painting in a tour-de-force work that rivals many 17th-century architectural interiors by Dutch painters of the Counter-Reformation. Now known as the St. Charles Borromeo Church, the original structure was built just 50 years before the painting was made, from the exact type of marble that the artist painted on. A rare document of the interrelation between an artist’s material and subject, the painting reflects the cultural status of this church, which was celebrated for its reverberant light and use of a type of marble that had previously been employed exclusively in Italy.

Portraiture in the High Renaissance sought to express the essence of an individual’s soul and character as reflected in his or her physiognomy. Sofonisba Anguissola, one of the most accomplished painters of her time, was highly regarded for this skill. An oil portrait she painted on slate, presumably of her brother Asdrubale, has a charged animation coupled with reserved stillness. Anguissola’s mastery in drawing the facial features and her range of tonal colors for the garment underscore the sitter’s mood of pensive interiority. The painting may have been made while she was in residence at the court of Madrid. Knowledge of stone paintings in 17th-century Spain is still evolving, but Philip II owned several, including one by Titian.

Art historian Laura Gelfand, in her catalogue essay on 15th-century artistic practice, examines the subtle symbolic distinctions between medieval and early-Renaissance artworks made 80 to 100 years prior to the exhibition’s selections. Her discussion of how artists played upon the alchemical and illusionistic capacities of paint (to compete or collaborate with nature) enhances our understanding not only of these otherwise slippery artistic timelines but also enriches our thinking about contemporary practice. Today, painters are still taken with the endless illusionistic possibilities of pigments made from ground stones and suspended in a binding medium as a vehicle for the magic of realism. We still attempt to highlight or surpass the inherent beauty of our raw materials.

The notion of a work of art lasting unto eternity may be challenging to imagine; most things deteriorate over time as a result of environmental, climate, and human forces. Nevertheless, the transformation of lithic material in works of art resonates in more recent practice, such as in the Earthworks of Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt of the 1960s–70s, the contemporary sculpture of Maya Lin, and the revival of classical architectural painting and conservation techniques by specialists at Evergreen Architectural Arts in New York City. “Paintings on Stone” reminds us that the experiments and accomplishments of Renaissance and Baroque artists are never petrified but continually replenished as we uncover knowledge about the hidden treasures of the past and examine them through new lenses.