The martial aesthetic of the samurai is the theme of a new museum opening this month in Berlin.

By John Dorfman

In a utilitarian age, it is hard for us to imagine that the accoutrements of war could be beautiful. But for the Japanese in the age of feudalism, arms and armor were the subject of intense artistic effort. Aesthetics permeated every aspect of Japanese life, and war was no exception. Within the realm of military life, the samurai warrior class in particular developed its own particular artistic traditions and material culture. Today, the surviving objects that were created for the samurai are avidly collected both in Japan and in the West, testaments to a bygone age of deadly elegance.

Helmet with crests of evergreen holly, Nanbokucho period (1336—1392), iron, gold, lacquer,silk, unsigned.

Courtesy Samurai Museum Berlin

One of the top collectors of samurai-related material in the West is Peter Janssen, a German who acquired his first samurai sword (katana) more than 30 years ago and in the years since has amassed some 4,000 objects dating from the Kofun period of Japanese history to the Meiji period (6th century–19th century). Besides weapons and armor, his collection also comprises objects and artworks that relate to samurai culture, such as paintings and woodblock prints depicting samurai, textiles, tea utensils, and Buddhist sculptures. In 2017 Janssen founded the Samurai Art Museum in the Villa Clay neighborhood of Berlin, in order to share his enthusiasm with the public. As his collection continued to grow, Janssen decided to expand his museum to a larger facility in Berlin’s central gallery district, with a new presentation that includes immersive installations, enhanced by new technologies, that guide visitors through samurai experiences from the battlefield to the tea ceremony. Called the Samurai Museum Berlin, it opens on May 8.

Among the most striking pieces in the museum’s collection are the suits of armor, designed not only to protect the samurai from blows but to impress and terrify their enemies. These suits have an almost science-fiction quality to them, which can transform a man into a supernatural-looking figure of power. As an example, an elaborate Edo-period (18th–19th century) embossed ironwork armor, made by Myochin Munesuke, would have been for a samurai of very high rank. It was made with the uchidashi technique, which involves using punches of various sizes and shapes to push ornamentation patterns into plates of iron from the rear, and then shape the plates to conform to the body. Like many samurai suits of armor, it has a face mask with frightening, almost demonic expression, and its helmet is crowned with wing-like forms. Its component materials—iron, lacquer, silk, leather, brocade, and copper alloy—show that Japanese armor, unlike its European counterparts, was highly complex in terms of texture and color. Another armor in the Berlin museum, from the Momoyama period, displays the emblem of the rising sun and crescent moon, painted in red and black lacquer on the front and backside of the cuirass as well as on the ita haidate, or thigh-protectors made of lacquered rawhide scales. The iron plates on this suit have a gold leaf finish, which was reserved for high-ranking members of the samurai class.

Wakizashi Koshirae, Edo period (1615–1868), wood, ray fish skin, copper-silver alloy, iron, unsigned.

Courtesy Samurai Museum Berlin

The samurai rose to prominence during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), under the shoguns. Originally, they were employed by the emperor and by other nobility but became so powerful that they established their own regional governments. In the late 13th century, the samurai armies, aided by two major weather events in 1274 and 1281 (known as kamikaze, or “divine winds”), repelled the attempted Mongol invasions of Japan. This occurred despite the fact that the samurai were vastly outnumbered by the invaders, and the dramatic success gained them major credibility and popular acclaim throughout the country. It was around this time, in the early 14th century, that the Japanese swordsmithing tradition reached a new level of sophistication, based on the technique of laminating steel and tempering with heat treatment applied to different parts of the blade. The classic Japanese sword is a product of this craft and became closely associated of the samurai. To this day the sword is symbolic of samurai culture in general and the aristocratic warrior code of bushido. Sword guards (tsuba) were another field for creativity in Japanese arms design. The Samurai Museum Berlin has an example with an inlaid butterfly design, dating from the late Edo to Meiji periods and made from brass, gold, silver, copper, and mother-of-pearl.

Helmet and mask with embossed ironwork, Edo Period (18th–19th century).

Courtesy Samurai Museum Berlin

During the Tokugawa Shogunate in the 17th century, with feudal warring at a low ebb, demand for samurai on the battlefield declined, which moved many of them into a bureaucratic role. Although they occupied a middle position in the social hierarchy of Japan, in many cases they wielded major political power, as courtiers and administrators under the daimyo, or feudal lords. Some even became scholars. Those who were unemployed, having no lord, became known as ronin, or roving mercenaries, and these caused conflicts that became rich material for popular literature. In the mid-19th century, with the arrival of the American Commodore Matthew Perry and the opening of Japan to foreign trading presence and foreign influence, life for the samurai underwent another transformation. The introduction of firearms, long resisted in Japan, irrevocably changed their way of warfare. Starting in 1854, the year after Perry’s visit, the samurai were modernized in an organized fashion, with Western training and new technologies. In 1867, they once again took to the field to defend the emperor against rebellious nobles, part of a process that culminated in the firm establishment of centralized imperial rule. In 1868, the Meiji Emperor began his dramatic transformation and modernization of Japanese society, which spelled the death of the samurai—who by then numbered about 5 percent of the population—as a distinct presence in the military and political spheres. Members of the hereditary samurai families transitioned into leadership roles in modern Japan; even today, a large percentage of the business executive class is of samurai descent.

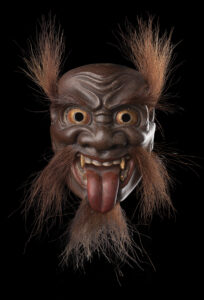

Helmet crest of an ogre (oni), wood, lacquer, animal hair, late Edo period, unsigned.

Courtesy Samurai Museum Berlin

In addition to the arms and armor on view at the Samurai Museum Berlin, there are other objects that speak of the cultural activities that went on in the samurai milieu, such as No masks and ukiyo-e color woodblock prints. The prints in particular show how the iconography of samurai armor fed the other visual arts. One on view is a triptych by Utagawa Hirokage titled The Great Battle Between the Troops of the Fishes and the Vegetables. Made in 1859, as the samurai age was drawing to a close, it depicts fish, fruits, and vegetables personified as warriors and dressed in samurai armor. The humor in this artwork may not have been whimsical but satirical—ukiyo-e were often a way to get away with lampooning authority by doing it in an indirect or symbolic manner.

Utagawa Hirokage, Great battle between the troops of the fish and vegetables, 1859, wood-block print, ink and colors on paper, vertical oban triptych: 35.9 x 73 cm.

Courtesy Samurai Museum Berlin

The age of the samurai age lasted around 700 years, from the 12th century, when massive clan conflict created opportunities for warrior nobles, until 1876, when the Emperor Meiji commanded the samurai to hang up their swords and let a modern army defend the nation. Modernization and Westernization killed off the samurai more effectively than any katana ever could, but their aesthetic did not die. It lives in the cultural memory of Japan, in contemporary Japanese popular culture, and in the passion of collectors such as Janssen. His museum in Berlin is a key destination for those who want to experience this unique military aesthetic first-hand.